“The Kek Wars” is a series of blog essays (2018) by author and occultist John Michael Greer that examines the strangest aspect of the 2016 U.S. presidential race: the convergence of online meme culture with occult practice in Donald Trump’s surprise victory. Greer’s central claim is that the election became a “magical conflict” – an unlikely battle involving internet trolls wielding chaos magick (symbolized by the cartoon frog Pepe and the faux-deity “Kek”) against the entrenched power of America’s political “aristocracy”. Throughout the series, Greer links the proliferation of pro-Trump memes and “meme magic” to age-old esoteric principles, arguing that modern politics can be understood in terms of symbolic warfare and archetypal forces normally studied in occultism and depth psychology. What follows is a structured analysis of Greer’s arguments, how he connects Pepe/Kek memes to chaos magick, his interpretation of subcultures like 4chan in occult terms, the broader cultural implications he draws, and critical perspectives on his thesis.

America’s Aristocracy vs. the Excluded: Central Themes of The Kek Wars

At the heart of “The Kek Wars” is Greer’s contention that magic is inherently political – specifically, “magic is the politics of the excluded”. In Part One, “Aristocracy and its Discontents,” Greer lays the groundwork by describing how those shut out of power often turn to magical or symbolic action as a last resort. He cites historical examples (such as the flowering of African-American folk magic under Jim Crow) to show that when conventional routes to redress are closed, disenfranchised people gravitate toward occult or “magical” solutions. By magic, Greer means “the art and science of causing changes in consciousness in accordance with will,” following occultist Dion Fortune. In other words, if you can’t change society directly, you attempt to change minds – starting with your own and radiating outward – through ritual, symbolism, and willpower. This sets the stage for his analysis of the pro-Trump meme movement as an emergent form of grassroots magic practiced by society’s outsiders.

Greer argues that leading up to 2016, the United States had developed a managerial elite – a de facto aristocracy – that defined the narrow range of acceptable political ideas and shut out dissent. Both major parties, he says, embraced an orthodoxy (sometimes tagged by alt-right thinkers as “the Cathedral”) which insisted “There Is No Alternative” to its policies. These policies, in Greer’s view, included globalization, offshoring jobs, onerous regulations favoring big corporations, and tacitly encouraging illegal immigration to supply cheap labor – all of which impoverished the working (wage-earning) class. The “excluded” thus included not only racial or ethnic minorities but millions of economically dispossessed Americans across demographic lines. Meanwhile, the privileged “aristocracy” (politicians, corporate leaders, the professional–managerial class) lived in a “self-referential bubble” insulated from the real consequences of these policies. Greer describes this ruling class as convinced of its own moral superiority – “the Good People, the morally virtuous people” – who use rigorous virtue signaling to distinguish themselves from the “deplorables” they exclude. This, he suggests, is typical of an aristocracy: it justifies its power by branding itself as inherently better (more enlightened, progressive, etc.) than those outside its circle.

In Greer’s analysis, by 2016 the tension between the “excluded” and the “excluders” reached a breaking point. The bipartisan elite consensus had foreclosed genuine debate on issues important to the working class, creating what right-wing neoreactionaries termed “the Cathedral” – “the enforced consensus of the mainstream, the set of values and beliefs that justify the existing order of society and, not coincidentally, the privileged place of the managerial aristocracy in that order”. In response, dissidents and “losers” of the system gravitated toward whatever ideologies the establishment found most unthinkable. Thus, a wild array of anti-Establishment ideas – from neoreactionary monarchism to neo-fascism to occult Traditionalism – swirled together under the loose label “Alt-Right”, unified less by a single doctrine and more by a shared rejection of elite sanctities. Greer is careful to note that the Alt-Right in this sense was not monolithic or entirely focused on race; he even calls the media’s fixation on racism a “straightforward disinformation” tactic by elites to prevent populist unity. The key point is that alienated young people – many of them chan (4chan/8chan) denizens – were rallying around Trump precisely because he defied the Cathedral’s consensus. The stage was set for a very unconventional battle, one where memes, jokes, and occult symbols became weapons of political insurgency.

Pepe the Frog, Kek, and Chaos Magick: Meme Culture as an Occult Practice

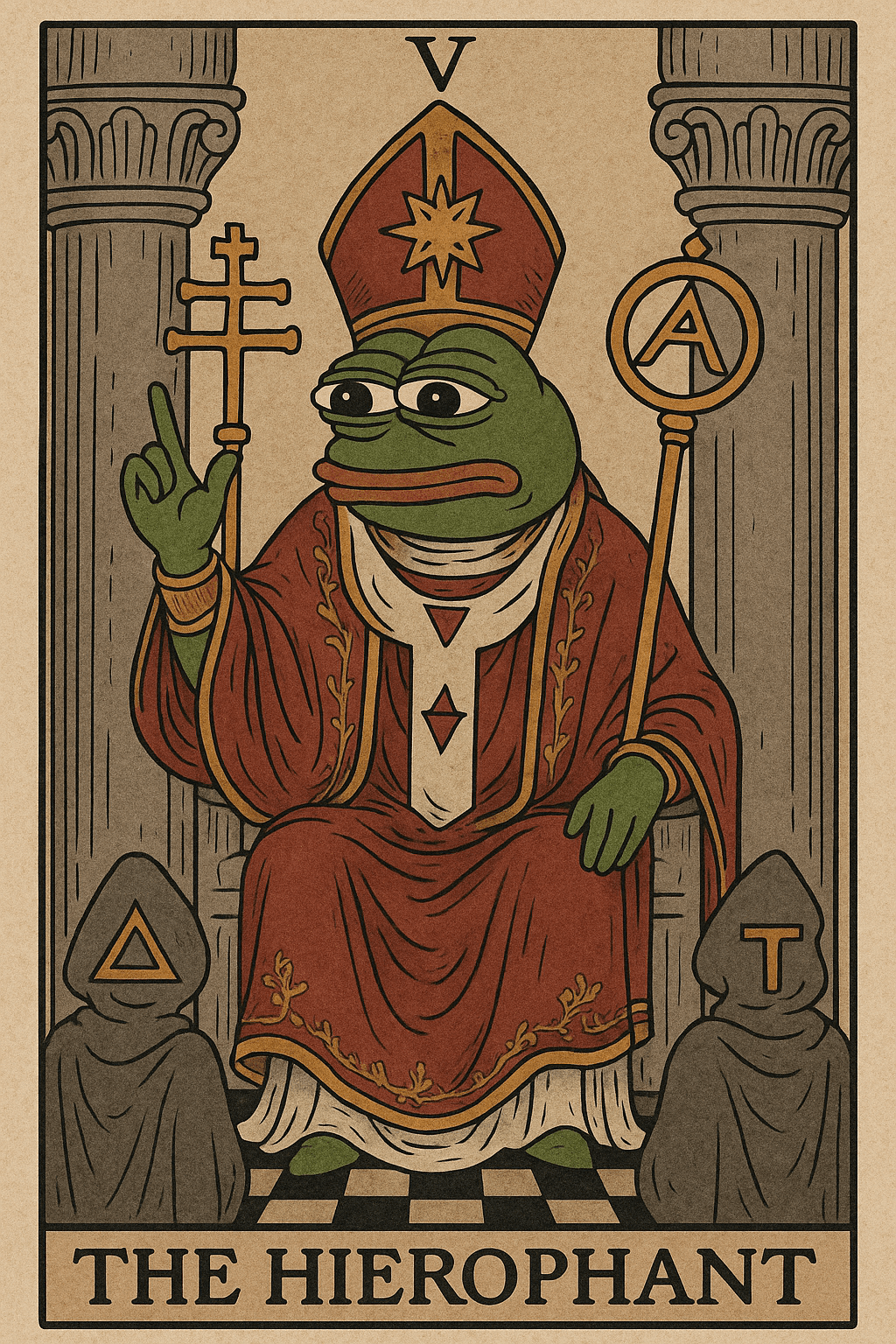

One of the most fascinating aspects of Greer’s series is how it links the irreverent meme culture of online forums to authentic chaos magic practice. Chaos magick (a postmodern form of occultism) emphasizes belief as a tool and often uses symbols or sigils in fluid, tongue-in-cheek ways to effect change. According to Greer, this was a natural fit for the prankster culture of 4chan. In Part Three, “Triumph of the Frog God,” he recounts how “thousands of disaffected young people who’d been shut out of…privilege…turned to magic”, specifically chaos magic, because it was “readily accessible and well suited to the work at hand.”. In practice, these channers began treating memes as magical sigils – stylized images and phrases imbued with intent – to influence reality in Trump’s favor.

Greer describes a snowballing series of “strange and meaningful coincidences” that convinced the 4chan community they were on to something powerful. Users noticed, for instance, that posts about Trump on the /pol/ board kept generating “gets” – lucky post numbers with repeating digits, which chan lore treats as significant omens. On June 19, 2016, one anonymous user typed “Trump will win” and, by chance, got the coveted post #77,777,777 – a perfect lucky 7 alignment. Around the same time, users began to joke that “kek,” their slang for laughter (analogous to “LOL”), had a deeper meaning. Remarkably, they discovered “Kek” was the name of an ancient Egyptian god of primordial darkness, often depicted as a man with a frog’s head – an eerie echo of the cartoon Pepe the Frog that had become their unofficial mascot. One user dug up a photograph of an Egyptian frog statuette mislabeled “Statue of Kek” – in fact a statue of the frog-goddess Heqet – noting that the hieroglyphs on it resembled a person seated at a computer with magical energy swirling out of the screen. The chan boards lit up with amusement and amazement: was this mere coincidence, or a synchronicity hinting that Pepe was an avatar of something cosmic?

Before long, a tongue-in-cheek yet earnest narrative took hold: Pepe the Frog was the earthly form of the chaos god Kek, who had chosen Donald Trump as his champion. Trump’s unlikely rise was interpreted as divine favor – or at least “meme magic” – at work. Greer notes that many on the chans “acted as though they were convinced that Donald Trump was the anointed candidate of the god Kek, bringer of daylight, who had manifested as Pepe the Frog and was communicating his approval…with ‘gets’.”. In true chaos-mage fashion, belief and satire blurred: whether they literally believed this or treated it as an elaborate in-joke didn’t matter, so long as they behaved “as though” it were true. Thus empowered by a meme deity, the “operative mages” of /pol/ began directing their will toward real-world results. Greer recounts that in mid-2016, rumors about Hillary Clinton’s ill health were circulating, so the 4chan magicians collectively focused on one clear intent: “make Hillary Clinton collapse in public.”

On September 11, 2016, the saga reached a dramatic crescendo. That day, three events unfolded in succession. First, Hillary Clinton – perhaps unwittingly amplifying the meme – publicly denounced Pepe the Frog as a “hate symbol,” lending the froggy chaos-cult mainstream visibility (to the “great delight of the chans” who loved the free publicity). Second, only hours later, Clinton indeed collapsed on camera while leaving a 9/11 memorial event, exactly the sort of public stumble the memers had envisioned. Video of her being hauled into a van “like a sack of potatoes” went viral. The chan magicians were stunned – even a bit frightened – by this apparent success of their working. Greer explains this reaction with an occult in-joke: in magic circles there’s an acronym “TSW” – “This Stuff Works” – used to describe the unsettling moment a novice realizes their spell had a real effect. September 11 was the TSW moment for the meme magicians, who suddenly felt that maybe their Pepe sigils and Kek rituals were more than just LARPing.

And then came the third twist of that day: another anon stumbled upon a forgotten 1986 Italo-disco song titled “Shadilay.” The song’s album cover featured a cartoon frog wielding a magic wand, and the band’s name was P.E.P.E. – an almost unbelievable coincidence. This discovery hit 4chan the same day as Clinton’s Pepe denunciation and collapse, and it was received as a sign of divine affirmation: proof that Kek was real and sending his froggy blessings across time. “Shadilay” was immediately adopted as the unofficial anthem of the Kek cult, and “Shadilay!” became a memetic cry akin to a religious exclamation for the faithful (“the same status for Kek’s faithful that ‘Allahu Akbar!’ has among devout Muslims,” Greer quips). By now, the chan community’s ironic devotion to Pepe/Kek had escalated into what Greer calls “frantic intensity”. The “Cult of Kek” was in full swing in the final weeks of the campaign: Trump was their prophesied “God-Emperor,” Pepe was a sacred sigil, and every meme, post, and digital prank was a magical volley in the larger war. Greer suggests that if Trump had issued a truly outrageous command to his chan acolytes at that moment, “there’s a fair chance they would have done it” – such was the fervor stirred by this bizarre blending of internet humor and occult mindset.

In Greer’s interpretation, the Pepe/Kek phenomenon directly links online meme culture to chaos magic practice. The memes were not just jokes but intentional acts of enchantment. He frames political “memetic warfare” as literal magical warfare: the repeated sharing of images and catchphrases worked like incantations, focusing collective psychic energy toward an outcome. Importantly, Greer notes that chaos magick’s “postmodern” style (with its flexibility, irony, and mix of pop-culture symbols) made it especially suitable here. The chan memers might not have been formally trained occultists, but by experimenting with belief and symbolism – and by “weaponizing Pepe” – they were, in effect, casting spells on the culture. Greer’s account thus elevates the Pepe meme from a trivial alt-right mascot to a key that unlocks how 21st-century media and psychology can create real-world impact through symbolism. Even those skeptical of literal magic can acknowledge, as Greer implies, that the “meme magic” narrative became a potent motivating myth for Trump’s online base, which may have influenced enthusiasm and turnout in non-negligible ways.

4chan as the Cauldron of Chaos: Internet Subcultures and Magical Framing

Greer places considerable emphasis on 4chan and related forums (often collectively dubbed “the chans”) as the locale where this modern magical movement brewed. These boards, he explains, are anonymous, minimally moderated spaces where “anything goes – the more offensive to the conventional wisdom, the better.”. In Part Three he introduces 4chan’s origins (spun off from a Japanese anime forum) and notes that it had “a significant impact on internet culture” long before Trump – for example, inventing the famous “lolcats” meme format. Boards like /pol/ (“Politically Incorrect”) became gathering points for “young and disgruntled” individuals to vent about topics banished from polite discourse. In Greer’s analysis, 4chan functions almost like the collective unconscious of the internet, a chaotic wellspring of repressed thoughts and images. By “plunging into” this fringe environment, the nascent Trump movement tapped a raw cultural energy that the mainstream had ignored or scorned.

Crucially, Greer interprets the activities on 4chan not just as political extremism but as magical acts. He explicitly describes the pro-Trump netizens as “a band of outsiders…armed with the tools of chaos magic” who waged an occult memetic campaign. The 2016 election, in this framing, became a contest of spells: on one side, the chan magicians conjuring a narrative of Trump’s destiny via Kek; on the other, the establishment weaving its own enchantments (the “magic of the excluders”) to maintain consensus reality. Greer actually asserts that both sides of America’s split employed magic in different ways: “the excluded [use magic] to seek change, [and] the excluders to convince themselves that there’s no need for change.” In earlier parts of the series he hints at the “inversion” that elites too practice a form of magic – albeit a debased one – through things like mass media, PR, and the rituals of power. For example, Greer points to the elaborate performances of moral virtue by the privileged (their “ornate code of virtue signaling”) as a kind of social magic that maintains their cultural dominance. Thus, while 4chan’s foot soldiers were summoning Kek, the Clinton campaign and media were performing their own enchantments – casting Trump as an absolute villain, reinforcing the inevitability of progress, and so on. Greer provocatively describes the clash as “when those two kinds of magic collided, the Kek Wars broke out.”

One vivid way Greer underscores the chan’s role is by referencing Carl Jung’s theories. In Part Four, he invokes Jung to make sense of the “cascade of meaningful coincidences” around Pepe/Kek. Jung would call such coincidences synchronicities, evidence that deep psychic forces (archetypes) are moving beneath the surface of events. Greer suggests that 4chan – being an unfiltered id-like domain – is particularly susceptible to eruptions of archetypal content. He even analogizes the forum’s output (memes, obsessions, lore) to the symbolic images that bubble up from the unconscious during times of collective stress. In this sense, 4chan acted as a magical amplifier: an incubator where a group mind could coalesce around potent symbols (like the “Frog God”) and channel an archetypal force into the material plane of politics.

Greer’s framing turns the anonymous tricksters of 4chan into unwitting sorcerers. The site’s anonymity, transgression, and improvisational humor all served the chaos magic ethos well. Anyone could contribute a Pepe image or a new in-joke that, if resonant, would be iterated ad infinitum through the hive mind. This recall of egregores – occult thought-forms generated by collective belief – is strong: what began as a meme “for the Lulz” became an egregore of Kek, seemingly taking on a life of its own. Greer notes that once the Kek current was established, the chan magicians rallied “straight through Election Day” in an intense, ritualized fervor. From his perspective, online subcultures like 4chan provided both the ritual space and the rank-and-file army for an occult war. Rather than robed occultists in a secret temple, these were keyboard warriors on an imageboard, yet their impact – in Greer’s telling – was to inject myth and magic into what many assumed would be a mundane election. By mythologizing Trump’s campaign (casting him as a near-messianic figure defeating a corrupt order), the chan subculture helped frame the 2016 election in magical terms. This framing may not have been visible to “normies” at first, but in hindsight, Greer argues, it explains a lot about the passions unleashed during and after the election.

Archetypes Unleashed: Cultural Transformation and the Battle of Symbolic Systems

Beyond the immediate election, Greer views the Kek Wars as a symptom of deeper cultural and spiritual shifts. In Part Four, “What Moves in the Darkness,” he steps back to ask what was really happening on an archetypal level. The flurry of frog synchronicities and meme magic leads him to conclude that an archetype – a powerful primordial image in the collective psyche – had been activated. Greer reminds us of Jung’s insight: when symbols and coincidences start clustering in meaningful patterns, “something is moving in the dark places of the psyche”. In 2016, that “something” announced itself through Pepe/Kek and the unlikely ascent of a flamboyant outsider candidate. So, which archetype was it?

To answer, Greer draws a striking parallel with Jung’s famous 1936 essay “Wotan.” Jung observed that the sudden mass hypnosis of Nazi Germany could not be explained by ordinary politics alone – an archaic god-image had seized the German psyche. Jung identified it as Wotan (Odin), the storm god of wild inspiration and fury, long dormant but stirring in the German collective unconscious. The “hurricane” of Nazism, Jung wrote, was essentially Wotan reasserting himself – and he grimly predicted that once awakened, this archetype would drive events toward a cataclysmic Götterdämmerung (twilight of the gods). Greer invokes this example to suggest an analogous process was underway in America circa 2016: an archetypal force indigenous to the American land and psyche was rising. However, it wasn’t Wotan – that’s a European myth. Greer posits that “we must look elsewhere for the archetype at work in today’s politics.”

He finds a clue in Native American lore. Citing the work of Vine Deloria Jr., Greer notes that Western culture forgot the “spiritual importance of place,” but the spirits of the land remain active. Many Native traditions across North America speak of a mythic being whose role is to change the world and make it fit for humans – often known simply as “the Changer.”. This figure appears under various guises in different tribes’ stories (for example: the Moon in some Salish tales; a dragonfly named Daldal for the Takelma; the Trickster Coyote in parts of the West). Sometimes the Changer is a hero, sometimes a clown or an “incomprehensible force,” but the common theme is: “The world was different once, and then the Changer came and made it the way it is now.”. Crucially, these tales have a distinct structure: they follow the Changer’s journey as he travels through the land, encountering one challenge after another. Each time, those invested in the old order attempt to stop him, and each time the Changer thwarts them – often by transforming them. There’s no single apocalyptic showdown; instead, it’s an episodic series of reversals. Greer recounts one such story: as Moon the Changer walks upriver, he meets a man intent on killing him with a wooden board; Moon casually turns that man into a beaver, saying “From now on your name is Beaver,” thus permanently diverting him from further trouble. Next the Changer meets another who tries to stab him with spiked weapons; Moon sticks those on the man’s head and christens him Deer, fating him to harmlessly graze instead of stopping change. And so it goes, until the Changer finishes his journey and departs (often leaping into the sky or becoming part of the landscape), “leaving the world forever changed in his wake.”.

Greer invites us to “notice…how often this pattern is repeated in American history” whenever great social transformations occur. America’s upheavals rarely end in a neat winner-take-all battle (unlike, say, Waterloo decisively ending the Napoleonic Wars); instead, there’s a chain of events with partial victories and persistent resistance. Even the Civil War followed this model: Gettysburg was no ultimate resolution, just a turning point, and the struggle continued until the “old order” (Confederacy) finally exhausted itself. In Greer’s view, Donald Trump’s rise fits the Changer archetype’s template to a remarkable degree. He writes: “That’s the archetypal pattern I see unfolding in American life right now. I don’t happen to know of a Native American myth in which the Changer’s role is played by a frog with magic powers, but that does seem to be the situation we’re in now.”. Here Greer humorously acknowledges the bizarre modern twist – a magic frog – yet in all seriousness casts Trump (aided by Kek/Pepe) as an embodiment of the Changer.

Two features of the myth stand out as especially relevant. First, those who futilely oppose the Changer end up trapped in repetition, “unable to change.” Greer notes that in the stories, the beings who resist are left doing forever what they were doing when the Changer found them: the carver keeps carving (as a beaver), the lookout keeps looking (as a deer). He then draws a direct parallel to Trump’s opponents: “That’s exactly what Trump’s opponents have been doing since his candidacy hit its stride…‘From now on your name is Protester,’ says the Changer, and sticks a pussy hat on the person’s head and a placard in her hands…”. In Greer’s allegory, much of the anti-Trump “Resistance” has been reduced to a perpetual protest movement – marching, shouting, repeating slogans – stuck in a loop of outrage that achieves little (much as a beaver gnaws trees to no end). This is a striking interpretation of the post-2016 liberal activism, suggesting that by refusing to accept any change in the status quo, the establishment camp has incapacitated itself, living out a kind of enchantment cast by the Changer archetype.

Second, the flip side is that Trump/Changer simply keeps advancing from one crisis to the next, largely unfazed. Greer points out how Trump’s critics continuously believed “this or that scandal will surely stop him,” yet “incident follows incident, and he just keeps going up the river and changing things.”. The dramatic “grand dénouement” – the knockout blow that Trump’s foes desperately anticipated (be it impeachment removing him, the Mueller report disqualifying him, etc.) – never quite materialized. In Greer’s eyes, this isn’t just luck or stubbornness; it’s the pattern of an archetype unfolding true to form. Once an archetype finds a “human vehicle,” it tends to play out a predictable narrative arc. Just as Jung saw that the Wotan archetype would inexorably drive Germany toward a Ragnarok-like collapse, Greer implies that the Changer archetype propelling Trump will continue to bring disruption and transformation rather than a tidy resolution. In practical terms, this meant Trump’s presidency would upend political norms and that even defeat (say, in 2020) would not simply restore the old order – the world after the Changer’s passage is permanently altered. Indeed, Greer’s later commentary (and book The King in Orange) argues that the “cascading absurdities” of pre-2016 American politics have come home to roost, and a return to business-as-usual is impossible.

The broader implication Greer draws is that modern media and politics are far from purely rational – they are arenas of myth and magic. The 2016 election, in his analysis, tore the mask off America’s collective psyche: revealing on one side a quasi-religion of progress and entitlement (the Cathedral of the elites, with its “Good People” convinced of their righteousness), and on the other side an emergent counter-mythos (a chaotic revolt of the wyrd, complete with its own god-form, prophecies, and rituals). This has profound cultural implications. It suggests that behind our political polarization lies a struggle between symbolic systems – one side clinging to an old narrative (globalist liberalism cast as the only moral vision), and another conjuring a new, strange narrative out of internet culture and populist angst. Greer even traces the lineage of the anti-Trump “magic resistance” (those witches and meditators who cast spells to “bind Trump” after the election) to the New Thought and New Age movements of the American left. In his view, both left and right in America are tapping occult currents, though in different flavors: the left’s roots in positive-thinking mysticism (which Greer wryly says produced both prosperity-gospel self-help and “megalomaniacs possessed of a sense of entitlement inflated to cosmic scale” among certain Clinton supporters), versus the right’s embrace of a chaotic, trickster current exemplified by Kek. The Kek Wars, therefore, was not a one-off internet prank – it was a manifestation of an ongoing cultural metamorphosis. It highlighted how “symbolic actions can spill into real life”, how imaginal forces (memes, archetypes, magical thinking) can influence material events and reconfigure national identity.

Critiques and Counterarguments

Greer’s bold synthesis of meme lore and occult theory has drawn both intrigue and criticism. While many readers (including occultists and political commentators) found “The Kek Wars” thought-provoking, not everyone agrees with Greer’s premises or conclusions. Several critiques and counterarguments have emerged, questioning aspects of his analysis:

- Adopting Alt-Right Narratives: Some have cautioned that Greer’s use of Alt-Right terminology and frames might bias his analysis. For instance, a commenter on Greer’s blog argued that calling the liberal establishment “the Cathedral” (a term coined by far-right blogger Curtis Yarvin) is “an unhelpful term which serves to confuse and distract” from how American society actually works. The critic noted that the U.S. lacks a single, centralized dogma-enforcing institution (unlike an actual cathedral); rather, American social control often operates through decentralized Puritan-like moral consensus. From this view, Greer’s endorsement of the “Cathedral” concept might indicate he has “already [bought] into an egregore” of alt-right thought, potentially skewing his objectivity. In short, some feel that Greer’s framework echoes alt-right talking points (e.g. emphasizing class over race, portraying elites as quasi-sinister “priests” of a false faith) and thereby downplays other explanatory factors.

- Downplaying Racism and Bigotry: Relatedly, critics point out that Greer’s sympathetic portrayal of the 4chan magicians glosses over the genuinely toxic elements of alt-right subculture. Greer asserts that the alt-right’s reputation for racism was largely a smear by elites, and he focuses on class disenfranchisement as the driver of the movement. Detractors argue this is an overcorrection: while economic and class grievances were surely significant, it’s hard to ignore the overt white-nationalist and anti-Semitic currents that were present on 4chan/8chan and within the alt-right. Greer’s narrative of a heroic band of excluded magi united under Pepe risks romanticizing a movement that also had hate-fueled motives. A fair counterargument is that both things can be true – many Trump meme warriors felt marginalized and also indulged in hateful ideologies – but Greer’s emphasis might underplay the latter. This has led some readers to bristle at what they see as an apologetic tone toward the alt-right’s ugliness.

- Magical Causation vs. Metaphor: A more fundamental skepticism comes from those who question the causal role of magic in the election. Did memes and chaos spells really “influence the 2016 US Presidential Election,” as Greer’s series title suggests? Or is this framework primarily a metaphorical way to describe memetic social dynamics? Rationalist critics are inclined to the latter – that the Kek phenomenon was a colorful psychological warfare tactic or a collective placebo effect, not literal sorcery. From this perspective, the string of “synchronicities” (7777777, Hillary’s collapse, Shadilay, etc.) can be explained by probability and confirmation bias rather than supernatural intervention. These critics might concede that belief itself can have real effects – e.g. energizing a voter base – but stop short of accepting that an Egyptian frog-god had anything to do with Trump winning. Greer, of course, writes for an audience open to occult possibilities, but for general readers his claims can sound extraordinary. Even some occultists have debated whether the Pepe/Kek magic was cause or consequence. Notably, Greer was asked if the 4chan chaos magicians “successfully projected the Changer archetype onto Trump” or if perhaps the archetype was working through larger forces beyond them. Greer’s own view (shared in comments) was that “it wasn’t that the chaos magicians summoned the Changer; it’s that [the Changer] basically summoned them”, using their meme magic as one channel among others. This nuanced take still assigns a mystical agency to the events, which more skeptical commentators would reject.

- Pattern Fitting and Predictive Power: Some critics question the retrospective fitting of the Changer archetype to Trump’s story. It’s an elegant theory, but is it testable? Greer asserts that knowing the archetype lets one predict the trajectory (just as Jung “predicted” Nazi Ragnarok). Skeptics might respond that such predictions only seem obvious after the fact. For example, if Trump is a Changer who leaves the world transformed, what does that concretely mean? (As of 2025, one could argue the American political landscape has been permanently changed by the Trump era – an arguably validating point for Greer – but others might see it as part of a longer cycle or simply the pendulum of politics.) Additionally, if the Changer is an American archetype, one might expect it to recur; will future populist figures similarly “go up the river” of American life, and how would we know a new archetype from an old pattern? These are open-ended questions that some readers raise when evaluating Greer’s Jungian approach.

- Academic and Ethical Critiques: Outside the immediate readership, academics or mainstream political analysts might critique The Kek Wars for its lack of empirical grounding. Greer’s melding of occult philosophy with political commentary is certainly unorthodox. It risks attributing intention and coherence to what could be random memetic evolution (the “meme magic” might have been partly an elaborate joke that believers ran with). Moreover, there is an ethical dimension: by framing Clinton’s supporters as delusional aristocratic magicians and Trump’s as righteous chaos-bringers, Greer implicitly takes a side. Some left-leaning occultists have indeed felt that Greer’s series veered into partisan territory (even if he stops short of outright endorsing Trump). One reviewer diplomatically noted that “The King in Orange” (Greer’s follow-up book) is “a look at the 2016 election through the prism of Greer’s political opinions and magical experience” – and that “whether you agree 100% with his findings, [it] gives you much to consider.” This underscores that Greer’s interpretations are not universally accepted; they are stimulating, but require critical engagement and may contain confirmation biases of their own. For example, his assertion that America is only divided by class, not race or gender, is contentious – many would argue it’s both, intertwined.

In summary, counterarguments to “The Kek Wars” often center on the concern that Greer’s occult framework might simplify or sanitize aspects of reality. Did Trump’s victory come from meme magic or from a confluence of sociopolitical factors (economic discontent, media strategy, foreign interference, etc.)? Greer would likely say “both” – with the latter providing the material conditions and the former the mythic catalyst that energized a movement. Still, readers should weigh his narrative against more conventional analyses. Even Greer’s admirers note that his perspective is just one lens; as one occult reviewer put it, the book (and by extension the blog series) contains “hard truths to swallow regardless of where your political beliefs lay” – implying that it challenges pieties on both left and right, but might not have the final word on these events.

Conclusion

John Michael Greer’s “The Kek Wars” series offers a rich and unapologetically strange interpretation of the 2016 election – one that fuses internet meme culture with arcane traditions of magic and Jungian psychology. Its central thesis is that beneath the surface of campaign rallies and Twitter debates, a battle of egregores and archetypes was being waged. Greer illuminates how a cohort of outsiders turned Pepe the Frog into a sigil of chaos magick, and how this participatory “meme magic” both reflected and amplified a populist revolt against the established order. He further argues that the tumult of 2016 signaled the resurgence of an American archetype – the world-changing Trickster/Changer – upsetting the country’s old narratives and power structures. This creative framework helps explain the quasi-spiritual fervor and uncanny coincidences that many noted in the election, casting new light on the role of symbolic systems (from viral memes to media-driven myths) in modern politics.

Whether one views Greer’s conclusions as literal truth, engaging metaphor, or provocative speculation, “The Kek Wars” undeniably expands the conversation about cultural transformation and political ideology. It suggests that technological society hasn’t banished magic after all – it has simply transmuted it into new forms, like pepe memes and hashtag sigils, which can be just as effective at “causing changes in consciousness in accordance with will”. The series has resonated widely enough to inspire further explorations (for example, an experimental documentary titled “You Can’t Kill Meme” was directly influenced by Greer’s essays and examines how the alt-right embraced chaos magic and symbolism in the 2010s). Greer’s work stands as a reminder that behind our political dramas lurk powerful stories and symbols – and sometimes, if we know how to look, gods and ghosts in frog’s clothing. In the end, “The Kek Wars” challenges us to take memes seriously and to recognize that human society, even now, runs as much on mythic imagination as on logic. It’s a wild thesis about a wild time – and as Greer himself wryly hinted, for those willing to entertain it, “you’re in for a wild ride.”

Sources: John Michael Greer’s “The Kek Wars” series on Ecosophia (Parts One–Four, 2018) and associated commentary; additional insights from Greer’s The King in Orange (2021) as reviewed in The Hermitage; You Can’t Kill Meme film review (Film Pulse); and discussions on Ecosophia forums.