On October 30, 1961, the Soviet Union tested the Tsar Bomba, a hydrogen bomb so powerful it remains the largest nuclear weapon ever detonated. Attached to the underside of a specially modified Tu-95 bomber, the bomb, officially designated izdeliye 602 or “item 602,” measured 26 feet long and weighed nearly 27 metric tons. When dropped over the isolated Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, it was not merely a military test but a symbol of the escalating arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

With an explosive yield of 57 megatons—around 1,500 times the power of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—Tsar Bomba’s detonation sent shockwaves across the world, both literally and metaphorically. Its mushroom cloud rose 40 miles (64 kilometers) into the atmosphere, and the blast wave circumnavigated the globe three times. If detonated over a populated area like New York City, the consequences would be unimaginable. Through the lens of Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, we can explore not only the physical impact of such a weapon but also the existential implications of humanity’s mastery over such destructive power.

Immediate Effects of Tsar Bomba on New York City

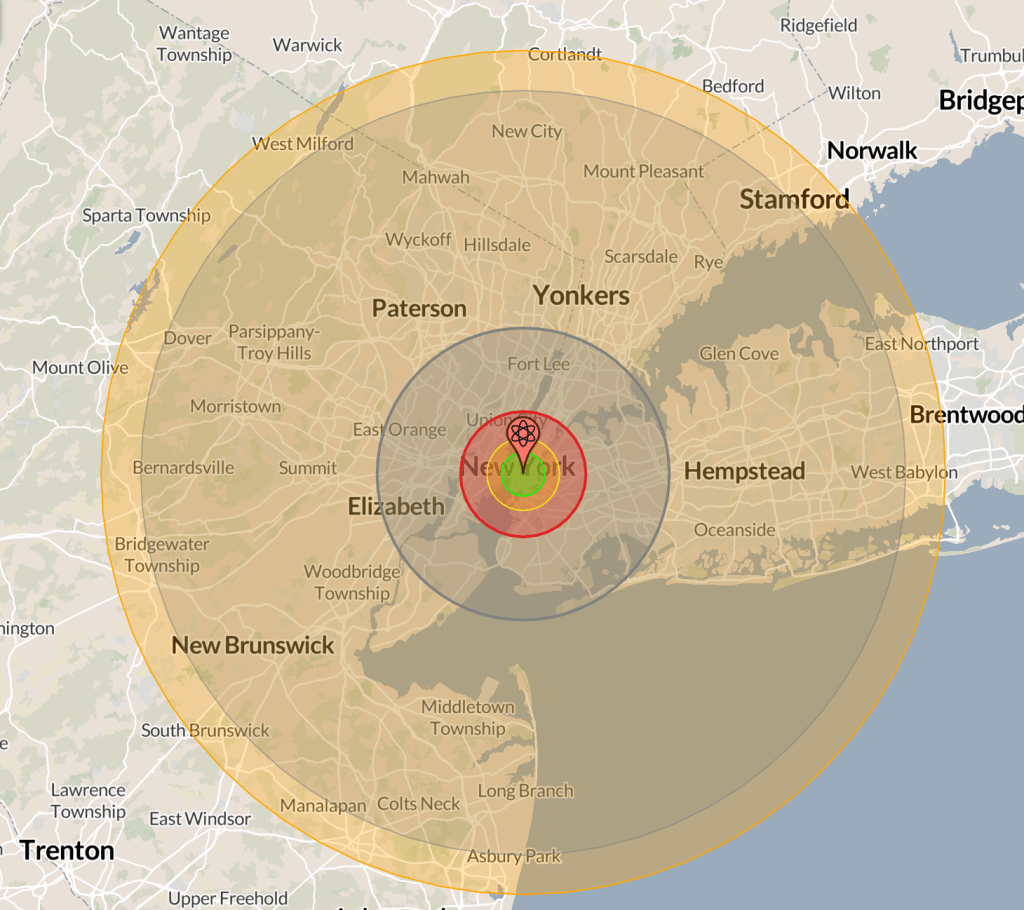

If Tsar Bomba were detonated over Midtown Manhattan at an altitude of approximately 3,960 meters (13,000 feet) to maximize blast radius while minimizing fallout, the results would defy comprehension. The bomb’s 5.16-kilometer-wide fireball would instantly vaporize everything within an area of 83.6 square kilometers. This radius encompasses landmarks like the Empire State Building, Central Park, and Grand Central Terminal. Temperatures within this radius would reach several million degrees, turning steel, concrete, and human bodies to vapor within seconds. Every structure and person within this zone would be reduced to ash, covering much of Manhattan and parts of Queens and Brooklyn, resulting in millions of fatalities.

Beyond this initial vaporization zone, the bomb’s effects continue to radiate outward with deadly force:

- The radiation radius of 500 rem, where radiation exposure would be fatal in about a month for most people, extends 3.14 kilometers (30.9 km²) from the blast. Survivors in this area would suffer high cancer rates, with 15% of those exposed dying from long-term effects.

- Within the heavy blast damage radius of 8.91 kilometers (249 km²), nearly all buildings, including heavily built concrete structures, would be demolished or severely damaged. Fatalities in this area would approach 100%, covering not only Manhattan but parts of the Bronx, Jersey City, and sections of Queens.

- The moderate blast damage radius of 20.7 kilometers (1,350 km²) would extend across most of New York City, into Long Island and suburban areas in New Jersey. Here, most residential buildings would collapse, fires would spread uncontrollably, and injuries would be near-universal.

Casualties: In this hypothetical scenario, 7.6 million people are estimated to be injured, with 4.2 million fatalities. With 16.3 million people within the broader blast range, these numbers emphasize the bomb’s ability to obliterate a densely populated area.

The thermal radiation radius of 60 kilometers would cause third-degree burns to anyone exposed. This radius, covering 11,300 square kilometers, would reach well into New Jersey, Long Island, and parts of Connecticut. In this area, people would experience third-degree burns severe enough to require amputation and intensive care, which would be unavailable due to the scale of the disaster. The light blast damage radius, extending 54.3 kilometers (9,270 km²), would see windows shattering in cities like Newark and even in parts of Connecticut, causing numerous injuries.

Fallout and Long-Term Contamination

While fallout effects are challenging to predict precisely due to factors like wind direction and human actions, we can estimate that an area spanning 50 kilometers around New York would suffer fatal radiation levels. Radioactive fallout would spread across the Eastern Seaboard, and contamination would likely reach as far as Canada and parts of the Midwest. In the aftermath of the actual 1961 test, radioactive fallout was detected in Japan’s rainwater, highlighting how quickly this invisible threat could travel. Long-term exposure would bring devastating health effects, including cancer, genetic mutations, and birth defects.

A Symbol of the Cold War’s Escalation

The Soviet Union’s decision to build Tsar Bomba wasn’t driven by tactical necessity but by Cold War posturing. At the time, the U.S. had a vast array of strategic bombers positioned close to Soviet borders, while the Soviet Union, lacking long-range missile capability, focused on building a bomb powerful enough to compensate for its limited delivery options. Initially, Soviet scientists aimed for a 100-megaton bomb, but concerns over fallout led them to scale back to 57 megatons. Ultimately, the bomb was too large to be practical. Military analysts recognized that deploying it would be nearly impossible, as its weight and size endangered the very planes carrying it.

The blast displayed Soviet might but also highlighted the terrifying limitations of this form of nuclear warfare. The shockwave caused the Tu-95 bomber to lose 3,281 feet in altitude upon detonation, underscoring the dangers inherent in deploying such a massive device. Afterward, the Soviet Union shifted focus to ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles), which could carry multiple warheads with precision, marking the end of the era of oversized nuclear bombs.

Heidegger’s Warning: Technology as a Force that Transforms Being

In “The Question Concerning Technology,” Martin Heidegger argued that modern technology is more than an assembly of tools; it is a force that shapes human existence and transforms the world into something to be controlled and exploited. Heidegger describes this phenomenon as “enframing”—a way of thinking that treats all things, including human life, as resources to be used, optimized, or discarded. Tsar Bomba, as the most powerful symbol of this technological mindset, represents the culmination of humanity’s willingness to wield absolute power over nature and existence itself.

The creation of such a device reflects a shift in humanity’s purpose, from creating and sustaining life to demonstrating dominion through sheer destructive force. According to Heidegger, this technological drive reveals a dangerous reduction of the world, where even cities and people become mere elements in a calculation of power. The bomb’s hypothetical detonation over New York City would reduce the heart of human culture and creativity to ash, in a single act that treats an entire metropolis as an expendable part of political posturing. “The will to mastery,” Heidegger writes, “becomes all the more urgent the more technology threatens to slip from human control.”

The Dangers of Calculative Thinking

Heidegger warned against what he called calculative thinking, a mindset that prioritizes efficiency, measurement, and control over the inherent value of existence. Calculative thinking reduces the world to a “standing reserve,” where every being and place is viewed through the lens of utility. The Tsar Bomba, designed not for practical use but as a display of dominance, embodies this mindset. It treats human life, culture, and history as expendable, reducing complex societies to mere statistics in a larger power struggle.

Detonating Tsar Bomba over New York would leave us with more than physical destruction; it would create a void where history, identity, and memory once existed. Calculative thinking, with its fixation on efficiency, fails to account for what would be lost in such a scenario. New York’s cultural fabric—its art, architecture, communities—would be annihilated, not as an act of war but as a demonstration of control. Heidegger’s critique forces us to confront this emptiness, to recognize that unchecked technological power does not elevate humanity but diminishes our ability to find meaning.

Reflective Thinking: Reclaiming the Value of Existence

Heidegger contrasted calculative thinking with what he called reflective thinking, a mode of thought that approaches existence as a mystery to be respected rather than as a problem to be solved. Reflective thinking would urge us to consider the ethical implications of our technological capacities, to see the world as more than a field for domination. In the case of nuclear weapons, this perspective would require us to question not only the utility of such devices but the very premise of wielding such power.

Reflective thinking invites us to ask: Why do we create weapons of mass destruction? What kind of world are we constructing when we allow such technology to define our relationships with each other? A world driven by reflective thinking would prioritize peace and preservation, recognizing that the ultimate cost of weapons like Tsar Bomba is a world increasingly devoid of meaning.

The Choice Before Humanity

The Tsar Bomba test remains a stark reminder of the potential for human technology to reach beyond reason and restraint. Its hypothetical detonation over New York City would obliterate millions, but the existential implications extend beyond casualties and destroyed landmarks. Heidegger’s philosophy encourages us to see Tsar Bomba as more than a weapon; it is a reflection of humanity’s relationship with technology, where power is pursued for its own sake, and existence becomes subordinate to control.

The lesson of Tsar Bomba is not only about the destructiveness of nuclear weapons but about the danger of allowing technological ambition to overshadow the inherent value of life and culture. In a world dominated by calculative thinking, we risk losing sight of being itself, sacrificing meaning for might. This bomb serves as a warning that the pursuit of absolute power does not create a stronger world but a diminished one, where existence is something to be annihilated rather than revered.

Through reflective thinking, we are called to recognize the perils of unchecked technological ambition, to choose a path that respects life, culture, and the mystery of being. In confronting the legacy of Tsar Bomba, humanity has the opportunity to redefine its relationship with technology—not as a tool for domination, but as a means of fostering a world that values existence over destruction.