Disclaimer: This abstract serves as a brief outline of a larger work. Research for this project is ongoing, but the authors felt it was important to present their initial findings. The full project will offer a more comprehensive exploration. It will include in-depth research and analysis. These findings will be presented in the final work.

Introduction

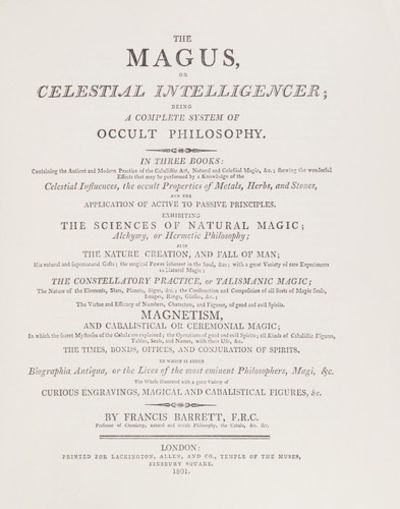

Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), introduced various innovative religious practices. These practices have long puzzled scholars. Among these practices, the true order of prayer is a central element of the LDS temple endowment. It stands out due to its apparent roots in Western esotericism. This abstract argues that the true order of prayer, as initially conceived by Smith, was influenced by the Western esoteric tradition. This tradition was particularly articulated in The Magus or the Celestial Intelligencer, a grimoire by Francis Barrett.

This abstract examines historical evidence, linguistic patterns, and the ceremonial context of the endowment. It seeks to show how Smith’s engagement with The Magus influenced a theurgical practice. It also examines how other occult sources informed this development. This practice is intended to summon divine messengers and facilitate spiritual ascent.

The Context of Joseph Smith’s Magical Practices

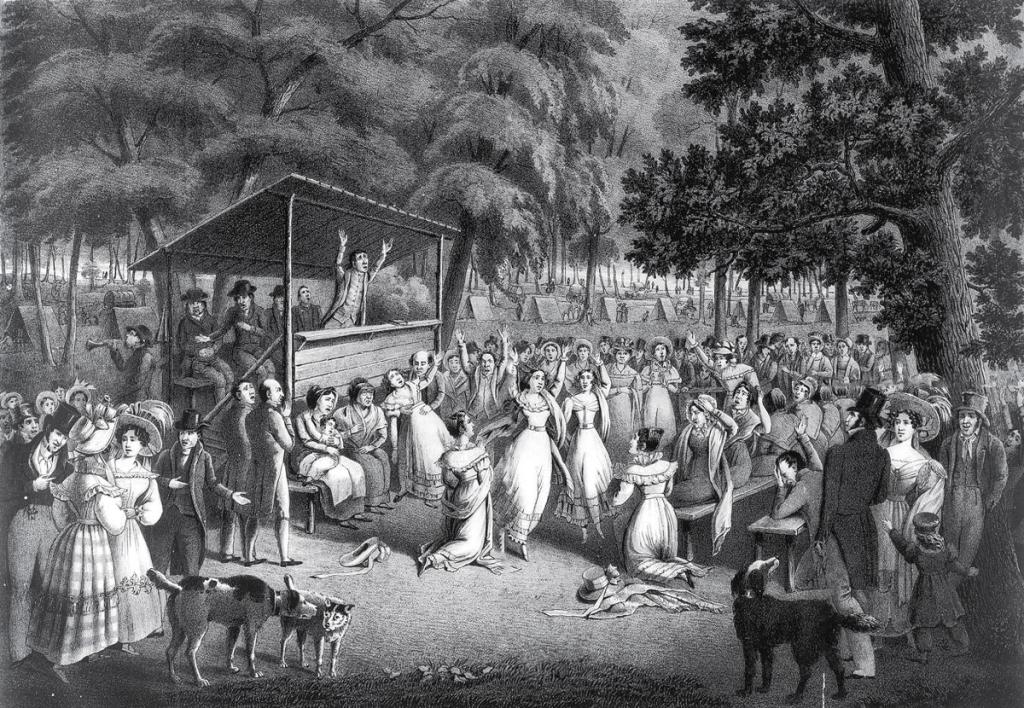

Joseph Smith’s upbringing in early 19th-century New England—a region known for its religious fervor. It had a rich folk magic tradition, which provides the backdrop for understanding his later religious innovations. The ‘burned-over district’ of upstate New York was characterized by a confluence of revivalist Christianity. It also had remnants of European magical practices. This term was coined to describe the intense religious revivals that ‘burned over’ the area. This environment was fertile ground for a young man like Smith. He was exposed to both the Bible and esoteric practices. He developed a syncretic religious worldview that combined elements of both.

Understanding Smith’s family background is also crucial. Like many others in their community, the Smith family participated in folk traditions. These traditions included treasure-seeking, the use of divining rods, and the creation of protective charms. These activities were not seen as contradictory to their Christian faith. Instead, they were seen as complementary tools that could be used to access hidden knowledge and divine power. This is a testament to the integration of folk traditions into their religious practices.

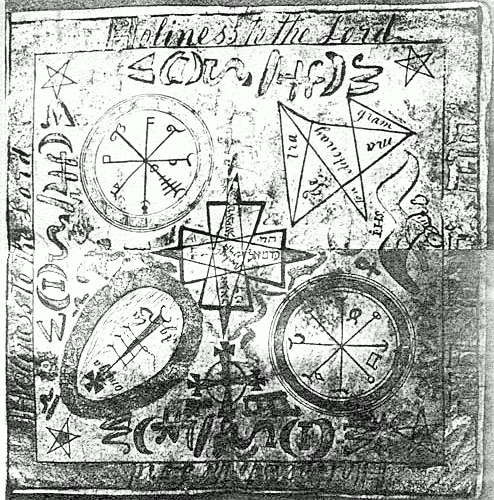

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence linking Smith to esoteric traditions is a collection of magical parchments passed down through Hyrum Smith’s line. At one time, these parchments were held by Eldred G. Smith, the last Presiding Patriarch of the Church. They are currently owned by Eldrige Smith’s estate.

[For an in-depth analysis of the parchments’ provenance, please see Nick Literski’s presentation on YouTube.]

These parchments contain a range of symbols and invocations that can be directly traced to The Magus and earlier works by Agrippa and other Renaissance magicians. These symbols are not merely decorative but are part of a coherent magical system designed to invoke protection and guidance from celestial powers. The presence of these parchments within the Smith family suggests that Joseph Smith was aware of these traditions.

The Role of Scrying and Astrological Timing

Another significant aspect of Joseph Smith’s early magical practices was using a seer stone. This practice, known as scrying, involves gazing into a reflective surface to gain hidden knowledge. It was common in early modern Europe. For example, John Dee and Edward Kelly used a black mirror in their Enochian workings. The practice also persisted in American folk traditions. Smith’s use of a seer stone for treasure-seeking was a practice he later adapted for receiving divine revelations, demonstrating his early reliance on this form of divination. It has clear parallels in the esoteric tradition of scrying as described in The Magus. Barrett described scrying as a legitimate method for communicating with spiritual entities.

The timing of Moroni’s visits to Joseph Smith, which coincided with the autumnal equinox, further aligns with esoteric practices. The equinoxes have long been regarded in various traditions as special times. These are when the veil between the physical and spiritual worlds is thinnest. This makes them ideal for summoning spirits or receiving divine messages. In esoteric traditions, including those outlined in The Magus, the alignment of celestial bodies is crucial for successful magical operations. Specific times of the year also play an essential role. Smith’s reception of divine messages during these times suggests he may have been following these esoteric principles consciously or unconsciously.

“Baurak Ale”: An Esoteric Identity

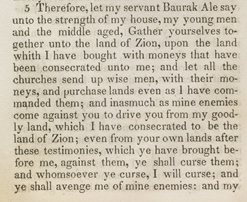

As Joseph Smith’s religious career progressed, he increasingly incorporated elements of esoteric traditions into his public and private practices. One of the most intriguing aspects of this development is his adoption of the pseudonym “Baurak Ale.” This is mentioned in in the 1835 edition of Doctrine and Covenants 103:21. This name has puzzled scholars and church members alike and appears deeply rooted in esoteric traditions.

The name “Baurak Ale” is likely variation of “Barachiel” or “Barachel.” These names are associated with one of the seven archangels in Jewish mysticism and Western esotericism. Barachiel, in particular, is related to the planet Jupiter, which governs expansion, protection, and divine justice in esoteric thought. In texts like The Magus, Barachiel is invoked for his protective qualities. This association with Jupiter is particularly significant. Jupiter was the astrological ruling planet of Smith’s day of birth, Thursday. More importantly, a Jupiter talisman was allegedly discovered among his personal effects after his death.

The talisman features the sigil of Jupiter and a magical square. It is identical to those described in The Magus. This includes a small printing error in that work. Barrett’s text outlines the construction and consecration of such talismans. These were believed to harness the power of planetary influences and were used to protect the bearer or bring about specific outcomes.

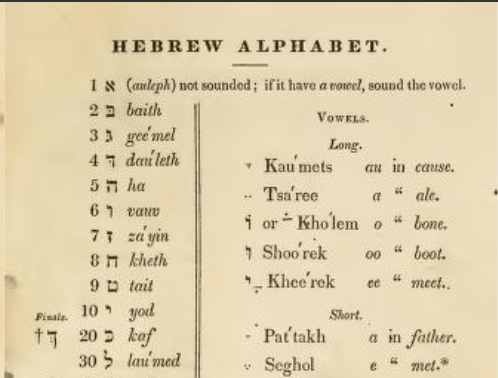

Further insight into the name “Baurak Ale” comes from Joseph Smith’s Hebrew studies under Josiah Seixas. Seixas was a Sephardic Jew who taught Hebrew to Smith and other early Mormon leaders in Kirtland, Ohio. Seixas’s lessons gave Smith a foundational understanding of Hebrew, which he then applied in his religious writings and revelations. The construction of the name “Baurak Ale” likely involved using Seixas’s transliteration patterns, which is aligned with the angelic name “Barachiel.” The angelic name extended Smith’s identification of dispensational heads with archangels. For example, in the Doctrines and Covenants, Adam is identified as Michael and Noah as Gabriel.

The True Order of Prayer and “Pay Lay Ale”

Now we turn to the focus of this abstract, the phrase “Pay Lay Ale,” used in the pre-1990 LDS temple endowment. When using the same transliteration methodology as with “Baurak Ale,” the phrase appears to be a transliteration of “Peliel.” This name is found in Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy and later included in The Magus. However, the name “Peliel” is rarely mentioned elsewhere, substantiating the claim that Smith found it in The Magus. It’s likely etymology is Hebrew for “the mouth of God,” suggesting that he is a divine spokesperson or intermediary. This phrase, therefore, plays a significant role in the true order of prayer.

In The Magus and other esoteric texts, invoking specific angelic names within a circle is central to theurgical magic. These names are believed to hold the power to summon divine beings or bring about specific spiritual effects. The use of “Pay Lay Ale” in the LDS temple endowment can be understood within this framework.

In the endowment ceremony, the phrase is not explicitly stated in the first instance, but its use is implied through the actions of Adam, who after being expelled from the Garden of Eden, builds an altar and prays. This act of prayer, based on the account in the LDS Church’s Book of Moses, results in the appearance of a divine messenger.

The first instance is crucial because it sets the stage for understanding the power of the true order of prayer in the endowment. Adam’s act of building an altar and praying, followed by the appearance of an angel, mirrors the methods described in Barrett’s work, where invoking sacred names and performing specific rituals are used to establish contact with celestial entities. The implication here is that Adam’s first prayer, though not explicitly articulated in the endowment as “Pay Lay Ale,” aligns with the esoteric practice of calling upon divine forces through ritual.

However, when Adam repeats the act of praying at the altar a second time, this time explicitly using the phrase “Pay Lay Ale,” Satan appears instead of a divine messenger. This moment in the ceremony introduces the essential theme of discernment between true and false messengers. Although Satan appears in response to Adam’s prayer, his inability to fulfill the requirements of a true messenger—specifically, the inability to shake hands as implied in the ceremony—exposes him as a false entity. This distinction is later solidified when Peter, who is sent by God, appears and gives Adam the first token of the Aaronic Priesthood, proving his legitimacy as a divine messenger.

Moreover, Smith’s teachings on testing spirits, outlined in Doctrine and Covenants 129, are consistent with the theurgical traditions found in The Magus. In this section, methods for discerning true divine messengers from false ones are provided—a critical concern in the Western esoteric tradition. The emphasis on testing spirits to avoid deception by malevolent entities reflects a common theme in ceremonial magic, where practitioners are taught to rigorously verify the nature of spiritual beings before trusting their messages. Incidentally, section 129 was revealed contemporaneously with the endowment.

The Behenian Fixed Stars

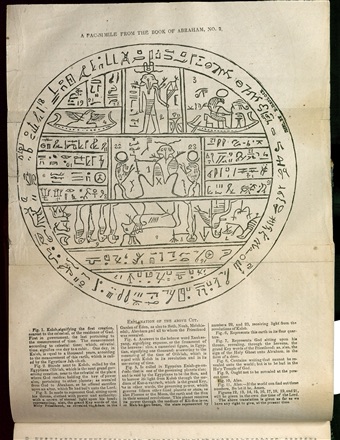

Joseph Smith’s integration of concepts taken from The Magus is further exemplified by his reference to the “fifteen fixed stars” in the Book of Abraham, specifically in Facsimile 2:

“Fig. 5. Is called in Egyptian Enish-go-on-dosh; this is one of the governing planets also, and is said by the Egyptians to be the Sun, and to borrow its light from Kolob through the medium of Kae-e-vanrash, which is the grand Key, or, in other words, the governing power, which governs fifteen other fixed planets or stars, as also Floeese or the Moon, the Earth and the Sun in their annual revolutions. This planet receives its power through the medium of Kli-flos-is-es, or Hah-ko-kau-beam, the stars represented by numbers 22 and 23, receiving light from the revolutions of Kolob.”

These “fifteen fixed stars,” which are also known as the Behenian fixed stars in Western esotericism, play a crucial role in astrological magic. In The Magus, these stars are described as points of powerful celestial influence, each associated with specific magical properties and ruled by a particular planetary force.

The inclusion of the fifteen fixed stars in the Book of Abraham suggests that Smith was embedding a sophisticated system of celestial correspondences into his teachings. This system aligns with The Magus, where each fixed star is linked to specific virtues and used in talismans to harness their power. The stars are considered “fixed” in the sense that they maintain a constant position relative to the celestial sphere, making them stable sources of influence in astrological practices.

In the context of the temple endowment and Smith’s broader theological framework, these fixed stars can be interpreted as symbolic of higher, celestial laws that govern both the physical and spiritual realms. Their inclusion in the facsimile aligns with the esoteric belief that the stars and planets exert a profound influence on earthly affairs and can be called upon to aid in spiritual ascent and revelation.

Moreover, this reference ties into Smith’s interest in the transference of celestial energy, as discussed in Doctrine and Covenants 88. This passage emphasizes the light and power that emanate from the stars and heavenly bodies, which resonates with the esoteric teachings on the influence of the fixed stars found in The Magus.

The 1990 Endowment Revisions: Moving Away from Esoteric Practices

In 1990, the Church removed “Pay Lay Ale” from the LDS temple endowment. This change was part of a broader effort to align the endowment more closely with mainstream Christian practices. It was also in response to anti-Mormon polemics such as the film The Godmakers. The decision to excise this phrase and other occult elements from the endowment can be seen as a response.

The endowment was stripped of this key theurgical element by removing “Pay Lay Ale,” initially intended to facilitate direct engagement with the divine. This change, among others, reflect a conscious effort to make the ceremony more accessible and less controversial to a global audience. However, these changes also represent a departure from the endowment’s original purposes as Joseph Smith conceived. This move effectively obscured the ritual’s original theurgical intent and deep connections to Western esotericism.

Conclusion

Historical and textual evidence suggests that Joseph Smith’s true order of prayer was deeply rooted in the esoteric traditions of The Magus. This practice was profoundly influenced by these traditions. This order of prayer was deeply rooted in the esoteric traditions of The Magus. Smith integrated elements from Barrett’s grimoire into the temple endowment. He created a ritual system to summon divine messengers. This system also facilitated direct revelation. The “Pay Lay Ale” removal in 1990 marked a significant departure from this original intent. It effectively transformed the endowment from a theurgical practice into a more symbolic and less explicitly magical ritual. This abstract has sought to clarify these esoteric dimensions. It offers a comprehensive and persuasive account of how early Mormon practices were shaped by Smith’s engagement with the occult.

References

- Barrett, Francis. The Magus, or Celestial Intelligencer; Being a Complete System of Occult Philosophy. London: Lackington, Allen, and Co., 1801.

- Agrippa, Henry Cornelius. Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Translated by James Freake. London: John Rodker, 1935.

- Quinn, D. Michael. Early Mormonism and the Magic World View. Revised and enlarged edition. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998.

- Seixas, Josiah. Hebrew Grammar. 1834.

- Doctrine and Covenants, Section 129. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1835.

- Doctrine and Covenants, Section 103:21. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1835.

- The Joseph Smith Papers. Explanation of Facsimile 2, circa 15 March 1842. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/explanation-of-facsimile-2-circa-15-march-1842/1

- Sacred Texts Archive. The Magus by Francis Barrett. https://www.sacred-texts.com/grim/magus/index.htm

- JSTOR. Joseph Smith and Magic: Palmyra and Beyond. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40629193